When it comes to matters microbiological, one of my favorite stops on the internet is Elio Schaechter's (and his fine co-bloggers) microbiologically-themed blog, "Small Things Considered." This blog has provided me with a great deal of fascinating, up to date, and insightful information that not only amazes my microbiology students, but delights me as well! I honestly feel that the "blog" approach to scientific papers can be very helpful to students pedagogically as they learn to read and analyze journal articles: distilling down complex papers to inclusive concepts, giving background to the "inside baseball" aspects of cutting edge research, and so on. Students agree it helps a great deal, particularly when they need to summarize and present papers, and I have ample evidence to back that assertion up. Several other people use a similar approach to cutting edge science as well, of course, including but not limited to Carl Zimmer, Ed Yong, and Laurence Moran.

However, Elio's blog is the place to go for Ongoing/Overwhelming Microbial Goodness™ (my version of the internet acronym "OMG"). Run, don't walk---electronically speaking.

Recently, Elio wrote a short essay at "Small Things Considered" celebrating art in microbiology, with many interesting and useful links. This is a particular interest of mine, and I thought I would comment a bit further on the topic. Elio is correct that there is a venerable tradition (perhaps started by Fleming himself, as is related in the blog post) of microbiology and art. The art can be whimsical (as with the "boxing bacteriophages" created by Fleming and reproduced in the blog post). It can be serious, as in the intricate and scientifically accurate art of David Goodsell. Here is a sample to illustrate what I mean:

The above would be Dr. Goodsell's interpretation of E. coli from a molecular point of view---based on what we know about the "machineries of life," which is also the name of a wonderful book by Dr. Goodsell. The description of the illustration above is here.

There are also artists who straddle the divide between the accurate and whimsical, and do it very well indeed. Michele Banks, as "artologica," does exactly that. Her many interesting artistic interpretations of biological concepts---including, famously, microbiology, can be seen at her Etsy shop. In fact, I once asked Michele to create a bit of artwork depicting predatory microbes, a subject I try to study with undergraduates in my laboratory. She asked for references about predatory microbes, and I sent them along. Her creation impressed me quite a bit, as it depicted many concepts from the articles I sent Michele. A nice blend of the artistic and the microbiological!

The places that artists can go with this topic are are a wonderful intersection between microbiological facts and artistic creativity. For example, here is E. coli created as a glass sculpture (link to the website describing the artwork here):

I can even go to a very odd place in this "sculpture business." Kombucha is a naturally occurring biofilm composed of yeasts and bacteria that ferment the drink of the same name from sugared tea. A Washington state artist, Nole Giulini, actually uses these biofilms to create sculptures, which she calls "Boschlings." Here is one, to give you some idea of the quirkily artistic results:

Ms. Giulini goes further and even has a YouTube video illustrating how to create and use the biofilm as a medium for her sculpture, complete with background music! What a remarkable intersection of art and microbiology, don't you think (even though the video description below describes kombucha as a fungus, when it is, again, a biofilm composed of various species of yeasts and several genera of bacteria, usually including Acetobacter xylinum)? Here is the link to the video, just in case my skills at embedding video are, um, underdeveloped.

In the last few months, another "microbiological art" approach has been described in the media. It is almost an analogue of photography, using UV radiation and the pigment producing bacterium Serratia marcescens. Zachary Copfer's interesting approach is described here. Below is an example of his approach, from that article:

So, as with Elio's blog entry, and the many links that can be found there and online, it is clear that it is possible to create art using microbiological topics or even microbiological material. Certainly, I have done my share with bioluminescent bacteria, as I have written earlier on this blog (including "portraits" painted with luminous bacteria, as Elio showed using an illustration my wife made of yours truly). Heck, my wife and I even put together a Microbial Xmas Tree last year, making "ornaments" from nutrient Petri plates, and drawing "stars" on them with luminous bacteria:

My involvement with microbiology and art began in an interesting fashion. Several years ago, I was asked to teach an "extra" lab section of Genetics at the University of Puget Sound (it was a huge class, and needed more lab sections taught than usual). In that class, I met a young woman who told me that she was interested in the intersection between art and microbiology---because some microbes, she knew, made pigments. True enough!

I had recently seen an interesting 2010 journal article by Charkoudian and her colleagues, describing how to use various species of Streptomyces as a source of pigment for student "art projects." It is a wonderful paper, describing using the "artistic" aspects of the pigment as a "hook" for teaching about microbial biosynthesis, chemical properties of pigments, the nature of paint, and some discussion of artistic principles, even when one of the sample products is not precisely "classical" (from the journal article). Viva, Streptomyces?

I was not able to obtain the "microbial palette" that actinobacteria can provide according to that journal article. But I did know that some of my "in stock" microbes produced interesting pigments: Chromobacterium violacein produces the purple pigment violacein, Serratia marcescens produces the red pigment prodigiosin (shown above and used by Zachary Copfer to make "Serratia photographs"), and Micrococcus luteus produces yellow carotenoid pigments.

The student in question, Kayla, was very excited by the possibilities. In collaboration with an organic chemist at the University of Puget Sound, the inimitable William Dasher, Kayla began to isolate pigments and begin to experiment with them in pigments (focusing on alcohol-soluble pigments for ease of work). As you can see, the results were lovely.

Kayla's best results were with violacein and prodigiosin, and she began to experiment with adding them to her paints. Soon she created some lovely print-panels of art---using microbes as their source and subject!

She finished by creating a triptych of artwork that stands to this day across from our departmental office (complete with an explanatory label)---and it is a source of continuing interest by visitors, and pride from students and professors alike. This is one of the goals of a small liberal arts institution: to mix science and the arts!

I have also had two wonderful "microbiology and art" experiences in my own classroom. These events demonstrate how art can extend and assist with pedagogy---especially for more "visual" students. It's not just about art: it can also be about learning---despite what a student might think while preparing for an exam!

Two years ago, I was doing what I could to keep my microbiology students (my "micronauts") engaged and attentive. So it is true I sometimes become a bit flamboyant as I lecture. I stood in front of one young woman in that class, Sarah, and told her that even as I spoke, I was emitting "Doc Martin associated microbes," just as she was doing the same thing with her own unique microbes---that there were clouds of microbes surrounding us at all times. I wondered aloud what was happening at the intersection of the two "clouds." Needless to say the grotesque (to the students) aspect of this discussion held their attention---and the topic of human emitted aerosols of microbes has in fact become of interest to scientists here and here.

But imagine my surprise, a year later, when Sarah (pictured next to her artwork) sent me the following piece of art (with apologies to Charles Schultz and the infamous "Pigpen").

Sarah is in dental school now, and is mindful of Microbial Supremacy, it is clear! I know that she will bring what she has learned (and is learning, now) to her practice as an excellent dentist. Especially when she considers how dental equipment "aerosolizes" microbes in the human mouth, as reported here. Gulp!

Last year, in my microbiology course here at the University of Puget Sound (and it is my only chance to preach the Microbial Gospel to students at my institution), I worked hard to find different ways to "reach" students who hadn't had much exposure to microbiology (forgive the pun, please). I created an extra credit "creative" assignment. I asked students to record short "video logs" describing what they found most interesting about microbiology. One student, Alena, said she was uncomfortable with such a project. Could she create a piece of artwork instead?

I thought it over, and suggested that Alena create a bit of art that depicted a biofilm, show that biofilms are composed of many species of microbes in nature, that antibiotics don't work well on biofilms, that bacteriophages can in fact attack biofilms, how biofilms disperse, and the role of quorum sensing in the formation and maintenance of biofilms. If you need to know more about biofilms (a topic which I think should be in the freshman curriculum, along with many other microbiologically-relevant topics) start here and then watch this.

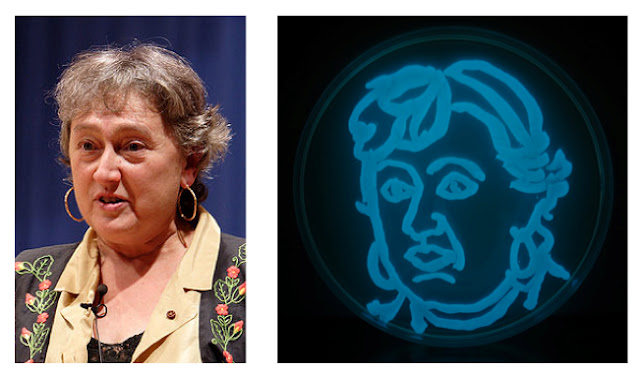

In any event, Alena accepted the challenge. Imagine my surprise when a week later, Alena presented me with the following (to the right of her photograph below):

What was most interesting to me was seeing how well she understood the process of biofilm formation (when I asked about it on their final exam)---because of her visual learning during the process of creating her cartoon art! This suggests that "artistic approaches" can be of genuine pedagogical value to many students.

Alena just returned from helping the Red Cross deal with Hurricane Sandy. I'm very proud of her, and think she will become a caring and superb physician.

It is increasingly clear to me that art and science can mix in ways that are of distinct advantage to both participants: new and interesting artforms can be created, and science can benefit from the visual in many ways (and at many levels). So the idea of "drawing" a fun cartoon on a Petri dish can in fact be used to illustrate important concepts in microbiology---and perhaps just as importantly, help students learn in nontraditional ways.

I wonder what will be next at this intersection of microbiology and art?

.jpeg)